Men’s Fashion

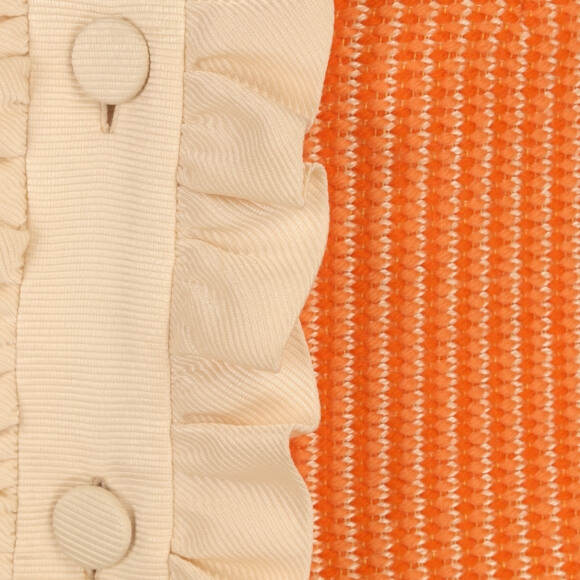

Motorcycle jacket (detail), Morris Leather Garments, 1950s. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Arthur G. Leith, M2001.87.1 © McCord Museum

While “men” and “fashion” were considered mutually exclusive terms from the 19th century well into the 20th, men’s clothing, no less than women’s, has been subject to changes in fashion that reflect shifting cultural, economic and political environments, as well as evolving perceptions of masculinity and femininity.

Suits have been an essential component of menswear since their introduction in the late 1600s. As the masculine ideal has changed, the fashionable suit has also been redefined. At the French courts of Louis XIV (1643–1715) and Louis XV (1715–1774), men wore brilliantly coloured fabrics and extravagantly adorned attire. The three-piece suit, consisting of coat, waistcoat and breeches made up in an embellished textile, was emulated by wealthy European men and transported to New France.

There, as in Europe, men’s clothing rivalled that of women’s in its brilliance, colour and embellishment, and men dressed flamboyantly without fear of social reproach.

A more active masculine fashion emerged in the late 1700s, inspired by the pastoral lifestyle of the British country gentleman. Its body-conscious tailoring emphasized a well-formed physique and featured subdued colours and durable wool fabrics. In the mid-19th century, with the growth of a powerful, self-made bourgeois class, the middle-aged industrialist became the new model of ideal masculinity. Eager to display his new-found wealth, yet wary of appearing “nouveau riche,” he favoured dark colours and avoided ostentation. The subtleties of careful tailoring, fine fabrics and a detailed dress etiquette communicated economic and social status. Merchants and industrialists looking to capture the confident style of this formidable ideal turned to local tailors such as Montreal’s Gibb & Co. Founded by Benaiah Gibb in the late 18th century, the firm catered to Montreal’s elite throughout this period, and until it closed in 1968.

A more youthful prototype of idealized manhood appeared at the turn of the 20th century.

Essential to a man’s active lifestyle was the versatile “sack suit,” with its shortened jacket. Originally intended for casual activities, the sack suit was considered appropriate business attire when made up in more formal fabrics and could even be styled into evening wear, known as the “Tuxedo jacket.” To this day, the sack remains the classic business suit.

In the early 20th century, a young, refined and worldly ideal was epitomized by the sartorial style of the popular Prince of Wales, who visited Canada in 1919 and 1923, and the elegant leading men of Hollywood films in the 1930s and 1940s. The interwar period of 1919–1938 is considered the heyday of men’s tailoring, with menswear produced by a variety of sources. While ready-to-wear manufacturers produced affordable good-quality suits, custom tailors were still in demand.

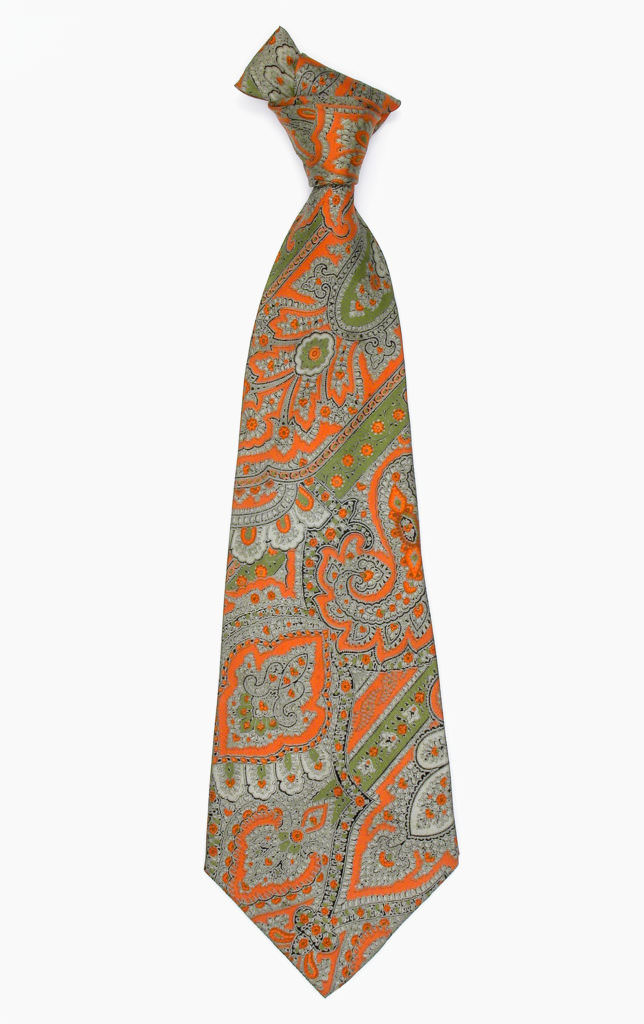

As the cultural movements of the 1960s and 1970s shook up established notions of male identity, men’s fashions began to once again incorporate bright colours, bold patterns and fabrics such as velvet and lace, a movement sometimes known as the “peacock revolution.”

Montreal’s Jacques de Montjoye (1928–) was a designer who took part in this wave to reinvent menswear.

Since then, popular culture has embraced a much broader spectrum of masculine ideals, including those from queer culture and other subcultures. The commercialization of masculinity has created space for a far greater range of fashion options, allowing men to flirt with overt display. In mainstream fashion, more conservative styles have nevertheless continued to hold sway for men, a holdover from a century and a half when social norms required that men’s interest in fashion be carefully circumscribed.

Share

DownloadRecommended entries

© MCCORD STEWART MUSEUM 2025