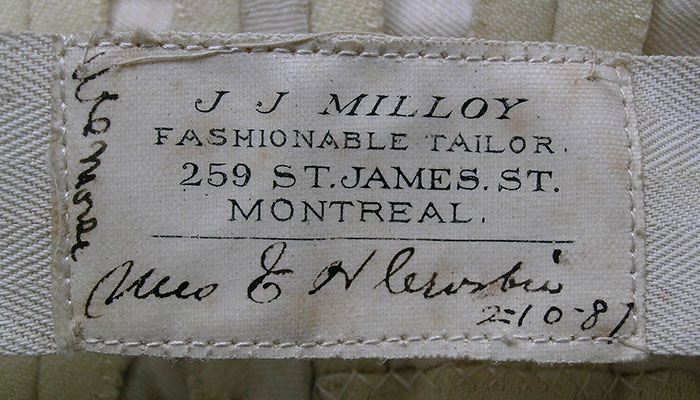

In the 1870s, John Joseph Milloy became one of Montreal’s most prominent merchant tailors, supplying both ready-to-wear and bespoke clothing to men from his shop, first known as St. Joseph Clothing Hall. Beginning in the mid-1880s at 259 St. James Street, he gained wide renown as a “ladies’ tailor,” developing a new market niche.

Two rare labelled garments in the McCord Stewart Museum collection attest to the quality of his work, and his innovation in the field of women’s wear.

Milloy’s story also sheds light on the excellent reputation that Montreal tailors enjoyed in the Northeastern United States, and the illegal cross-border trade that occurred as a result.

John Joseph Milloy was the middle child in an Irish Catholic family of five sons born in Naas, County Kildare. The family left towards the end of the wave of Irish emigration induced by the Great Famine. On June 9, 1853, when John was aged 4, the family arrived in Montreal amid the Gavazzi riots, a conflict where troops fired on an Irish Catholic mob protesting an anti-Catholic lecture.1

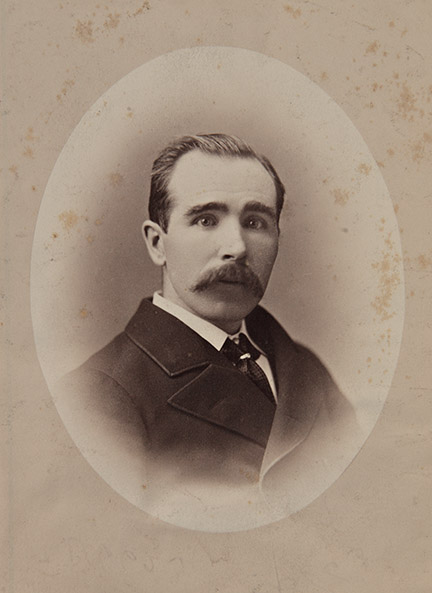

Notman & Sandham, John J. Milloy, Tailor, Montreal, 1877. II-46663.1, McCord Stewart Museum

Three years after their arrival, John’s father died. His death record identified him as a labourer. The eldest son became a landscape gardener, the second son a marble cutter, while the three younger brothers all went on to become tailors. Only John J. had enduring success in that business, and the younger two eventually moved on to other occupations.

There is no record of what tailoring training John J. Milloy received to prepare him for his future business. In 1870, he established himself as a merchant tailor. In 1874, he advertised that he sold both clothing and haberdashery; that same year he achieved a favourable credit score.2

By 1879, his advertising boasted that his was the largest clothing house in the city and employed the best cutting talent.

Most importantly, it informed a clientele of men visiting the city that he could make up garments on short notice.3 Milloy recognized a lucrative market outside of his local sphere.

Milloy was also quick to expand his market beyond the usual male clientele. By the 1880s, the fashion for women’s “tailor-made” dresses and suits was gaining ground quickly. Wool garments for women, particularly riding habits, had long been part of the male tailor’s repertoire, while garments made from silks and cottons were typically made by female dressmakers. In the last quarter of the 19th century, with women being more active outside the domestic sphere and in sports like tennis, golf, and cycling, the range of contexts in which wool ensembles were considered the most fashionable and practical attire also grew.

The mid-1880s were the turning point for Milloy’s expansion into tailoring for women.

In 1884, he took first prize for a walking dress, evening dress and cloak at an annual national exhibition of agricultural and commercial products.

In the 1885 edition of the humorous tourist guide, The Phat Boy’s Delineations of the St. Lawrence,4 his shop is not just described as Milloy, the tailor, as it had been in previous editions, but with the additional mention “where ladies’ tailor-made suits are a specialty.”

A portrait of Milloy’s wife taken in 1886 shows what is undoubtedly a wool tailor-made garment.

Wm. Notman & Son, Mrs. John J. Milloy, Montreal, 1886. II-81869.1, McCord Stewart Museum

In 1878, John Joseph had married Josephine Shea of Brooklyn, New York, the American-born daughter of Irish immigrants, who had completed her schooling in a convent near Montreal. They went on to have several children, who appear in a family portrait.

Throughout the rest of his career, Milloy’s advertising mentions this specialty of his house. An 1890 advertisement in a hotel guide for tourists mentions the range of women’s garments he could make up, including “suits, riding habits, wraps, Newmarkets, Ulsterettes, and street coats etc.”5

Milloy’s advertising for help suggests that his capacity expanded as he developed his female clientele.

From 1886 to 1888, roughly one third of his advertised positions were for workers specializing in women’s garments.6

In 1887, he advertised for three strictly first-class tailors to work on women’s waists, and two competent skirt hands, suggesting at least two distinct skill sets were required in the making of a garment. The extent of this advertising for help, however, may also suggest high employee turnover.

Over the decades, numerous new tailoring businesses advertised that their founders had worked with Milloy. The number of such start-ups suggests that Milloy played a significant role in training his competition, and that experience with him gave credibility to these new ventures. Most competitors did not last long in business, including Milloy’s younger brother Patrick Arthur who opened his own establishment in 1884, only to shut it down in 1887 and eventually become a well-known manufacturer of ginger beer.

By 1893, J.J. Milloy had clearly made a name for himself amongst women in the uppermost echelons of Canadian society, namely the wives of British peers.

In a letter dated that year from Lady Stanley, the wife of the outgoing Governor General, to Lady Aberdeen, the wife of the incoming Governor General, she warned that there was no good dressmaker in Ottawa. However, she recommended “a very good man for tailor-made dresses in Montreal, called Milloy; he is expensive and troublesome but can make very well.”7

Milloy had significant setbacks in his career that illuminate a little-known aspect of the Montreal clothing trade. By the end of 1885, US customs officials and the US Treasury Department had apparently been aware for over a decade that Canadian tailors were hiring agents in the United States to meet clients, take measurements and place orders for both men’s and women’s clothing. Rival Montreal men’s tailor Gibb, for example, had a New York agent during this period. The Montreal Winter Carnival, held five times between 1883 and 1889, was thought to be a significant factor in building Milloy’s reputation amongst his American clientele.

Milloy was often observed crossing the border with large suitcases but also apparently employed a sleeping car porter who was alleged to have slipped packages under the upper berths of sleeping cars. The Special Agent of the US Treasury for Vermont and Northern New York estimated that J.J. Milloy had brought $20,000 of clothing in this way for a decade, without paying the 45% duty. Milloy was one of a number of Montreal businessmen that customs agents had warrants to arrest if they crossed the border.

On Christmas Eve 1885, on his way to Brooklyn presumably to visit his wife’s family, Milloy was arrested in Plattsburgh, NY. His case went to court in the US and dragged on for years. In 1889, he pleaded guilty and paid a fine of $200. Since this fine was a far cry from 45% of $20,000, it seems the charges were lessened considerably.

In 1892, Milloy narrowly avoided being accused of smuggling a second time, but it came to light that a former employee, newly established in his own business, had bribed Milloy’s cutter and a U.S. customs agent to frame him in order to put him out of business.

The incident reveals something of the cutthroat competition in the field of tailoring in Montreal.

In fact, the cutter who bought out Milloy’s younger brother Patrick Arthur’s business in 1887 closed a year later, citing the fact that the city had a surplus of tailors.

In 1895, Milloy moved his shop away from St. James Street, settling at 2301 and 2303 St. Catherine Street, which was then located between McGill College Avenue and Mansfield Street. He stayed at that location for a decade, then moved briefly to a location on Peel Street, followed by one on McGill College Avenue, before closing his business around 1913. Both he and his wife passed away in 1937.

Milloy’s family was well known for another business in Montreal during this time. His mother and eldest brother’s wife operated a prominent bookstore, long located in an old house on the north side of St. Catherine Street, west of Bleury.8

Sources

1. Montreal Gazette, May 2, 1921.

2. Dun, Robert Graham. Mercantile Agency Reference Book, Montreal: Mercantile Agency, Sept. 1874, 89.

3. Phelan Brothers’ St. Lawrence Traveler, Montreal: Phelan Bros., 1879, 111.

4. Babbage, E. F., The Phat Boy’s Delineations of the St. Lawrence River and its Environs,4th ed. Rochester, NY: Post-Express Printing Co., 1885.

5. The Windsor Hotel Guide to the City of Montreal and for the Dominion of Canada, Montreal: J. Lovell, 1890, 121.

6. Advertisements published in the Montreal Daily Witness, 1886-1888.

7. Letter from Lady Stanley to Lady Aberdeen, September 2, 1893, MG27-IB5, Library and Archives Canada, quoted in Doris French, Ishbel and the Empire, Toronto and Oxford: Dundurn, 1988, 133, 326.

8. Montreal Star, February 2, 1911; Montreal Gazette, April 14, 1990.

Share

DownloadRecommended entries

© MCCORD STEWART MUSEUM 2025